Water added to waste equals dump debacles

The Akron Beacon Journal

PIKE TWP - Each day, several hundred tons of waste arrive at the 1,200-acre Athens-Hocking Landfill near Nelsonville, a small town in Athens County in southeastern Ohio.

As much as a third of that waste may be a grayish powder called aluminum dross, or salt cake.

It's kept in a separate area away from other trash and covered daily with dirt so that it stays dry, protected from rain and snow.

Landfill supervisor Nick Kunkler said the dross is being monitored "pretty heavily,'' and there have been no problems.

That's far from the situation 95 miles to the north in Stark County's Pike Township.

There, Countywide Recycling & Disposal Facility has accepted and buried more than 13 million tons of aluminum waste, mostly aluminum dross, since 1993. It wasn't kept dry.

That set off a chemical reaction that produced high temperatures and triggered an underground fire in an 88-acre section of the 258-acre dump.

The fire, which is believed to have started in late 2005, could threaten the integrity of the landfill's plastic liner and leachate- and gas-collection systems. It could also cause problems with slope stability and subsidence, or settling. Foul-smelling odors from the fire and the chemical reaction have plagued residents of southern Stark and northern Tuscarawas counties for months.

The Ohio Environmental Protection Agency is negotiating with Republic Services, the Florida-based company that owns and operates Countywide, on a plan to solve the problems at the landfill. If an agreement can be reached, the Ohio EPA would rescind the recommendation it made last month to deny an operating permit to Countywide.

But solving the problem -- slowing or stopping the chemical reaction/fire -- is likely to be difficult.

The amount of dross and other aluminum waste buried at Countywide -- 13 million tons -- is enough to fill Ohio State University's football stadium from the field to the top more than 30 times.

And Countywide is a wet dump, where leachate, or liquid runoff, has been recirculated through the buried waste.

Nothing simple, cheap

Jiann-Yang "Jim'' Hwang, head of the Institute of Materials

Processing at Michigan Technological University in Houghton, Mich., is an expert on aluminum dross. He said those factors mean the reaction/fire may continue in the landfill for "a long, long time.''

"I see nothing that is simple and cheap as ways to solve the problem,'' he said in a recent telephone interview.

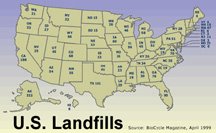

Under federal laws, dross, which is created when aluminum is recycled and remelted, is classified as nonhazardous waste. As such, it can be taken to any solid-waste landfill. No agency tracks where it goes.

But that could be changing.

In November, because of the heat and odor problems at Countywide, the Ohio EPA issued an advisory urging all landfills to use caution when handling dross and to cease circulating leachate through aluminum waste.

Countywide stopped taking all aluminum waste in July and stopped taking dross in 2001. American Landfill, another large landfill in southeastern Stark County, cut back on the aluminum waste it accepts. And dumps that are taking it, such as the Athens-Hocking Landfill in Athens County, are being closely watch by the Ohio EPA.

Smoke, fire, pollution

Ramon Mendoza, a spokesman for the U.S. EPA, said the federal agency is expected to release an advisory on dross in the next few weeks.

The Ohio EPA also is looking at tightening its rules on dross.

The reasons for doing so extend beyond the situation at Countywide.

• In November, a small above-ground fire was reported in dross at Wabash Alloy LLC's landfill for its aluminum waste in Wabash, Ind.

• Last March, an Indiana state inspector reported smoke believed to be from a fire in aluminum waste at the Wabash Valley Landfill in Wabash, Ind.

• In Kentucky, the Brantley Landfill at Island, the Fort Hartford Coal Co. limestone quarry at Olaton and Green River Disposal Inc. at Maceo have been declared EPA Superfund cleanup sites because of pollution problems caused by large volumes of dross. The dross caused underground fires, leaked into aquifers and streams and created ammonia fumes that bothered neighbors. The problems were discovered in the 1980s and corrected in the '90s.

• The Red River Aluminum site near Stamps, Ark., was declared a Superfund site after copper from aluminum dross dumped from 1988 to '98 leaked into a river. Ultimately, the dross had to be capped with clay and asphalt to stop the river pollution and keep water off the waste.

Despite these problems, aluminum dross isn't classified as hazardous.

U.S. EPA spokesman Mike Cunningham said that for waste to be considered hazardous, it must be dangerous or potentially harmful to human health or the environment. It must be on one of four federal hazardous-waste lists or be one of four characteristics: ignitable, corrosive, reactive or toxic under normal conditions.

Aluminum dross normally is inert. It creates problems only when it comes in contact with liquids. That makes it unclear whether dross could or should qualify to be classified as hazardous, Cunningham said.

For the most part, Ohio EPA staff members have concurred with that thinking, saying in memos that reactivity rules -- the area under which dross would most likely qualify to be hazardous -- are subjective and hard to define.

Efforts to regulate fail

But in 1994, Ohio EPA staffer John Palmer wrote a memo calling dross "potentially harmful.'' He advised the agency to consider dross "potentially inimical to human health and the environment.''

In the early 1980s, the federal government did attempt to have dross declared a hazardous waste -- something that would require extensive permitting, tracking and special handling and would cost the aluminum industry money.

But Barmet Aluminum Corp. sued the U.S. EPA, and a federal judge in Kentucky ruled that dross was nonhazardous.

Countywide started accepting aluminum dross in 1993, initially hauling the waste from Barmet's plant in Uhrichsville in southern Tuscarawas County.

According to Ohio EPA records, Countywide took in nearly 313,000 tons from a special cleanup from 1993 to '97, plus it accepted the Uhrichsville plant's day-to-day wastes -- totalling an additional 200,000 to 250,000 tons in that time.

At least five trucks carrying the aluminum waste to Countywide caught fire when the dross got wet, Ohio EPA records show.

For most of the 1990s, Countywide was owned and operated by Waste Management of Ohio. On May 4, 1993, Waste Management drafted a memo warning that the aluminum waste must be kept away from water and snow to avoid triggering a potentially dangerous chemical reaction. That memo was found early last month in the files of the Stark County Health Department, the agency that will make a decision about whether to approve an operating permit for Countywide.

In 1999, Countywide was sold to Republic Services.

A consultant for Republic -- the Wisconsin-based Cornerstone Environmental Group LLC -- reported in August that Countywide had accepted as much as 13 million tons of aluminum waste from the Uhrichsville plant and other sources from 1993 to July 2006.

The report said it was impossible to determine the chemical makeup of the material because of changes in aluminum manufacturing and raw aluminum materials between 1993 and 2006.

Will Flower, a spokesman for Republic Services, said the company has adopted a no-dross policy at all 58 of its U.S. landfills, although dross was buried only at Countywide and Wabash Valley in Indiana.

The aluminum waste requires "special handling and care,'' Flower said.

Stopping liquid is key

The problems at Countywide appear to be linked to a decision in 1998 to recirculate millions of gallons of leachate, or liquid runoff, through the landfill.

The Ohio EPA approved the request by Waste Management to do so, and Republic Services continued the practice when it took over Countywide.

"If we had known, we never would have recirculated our leachate,'' Flower said. "It was unforeseen and unseen in our industry on this scale,'' he said of the chemical reaction that occurred.

Countywide stopped the practice in early 2006.

The U.S. EPA's Mendoza said recirculating leachate is common in the solid-waste industry because it speeds up natural decomposition of garbage, and that creates more landfill space and results in money for landfill companies.

Since the Ohio EPA made its recommendation last month to deny an operating permit to the landfill, the agency and representatives from Republic Services have been negotiating on the findings at the dump.

Ohio EPA Director Chris Korleski has said he prefers a negotiated settlement with Republic Services because such an agreement could solve the fire and odor problems more quickly and with less legal expense.

Agency spokesman Mike Settles said the Ohio EPA will not comment on possible requirements that might be imposed until an agreement is reached.

For its part, Countywide officials have said there's no evidence a fire is creating problems with the landfill's liner or its gas- and liquid-extraction systems. The company has pledged to work with the Ohio EPA to resolve the problems.

Hwang, the Michigan professor, said it is difficult to comment on how the problem at Countywide might be solved because of the variables involved. These include the exact makeup of the aluminum waste and the design of the landfill.

The best thing to do might be to dig up the dross and ship it away for recycling, he said.

Or, he said, it might be possible to dig up the dross, treat it and then rebury it.

<< Home